After tonights lecture on Coast Salish culture:

What is one thing similar in Coast Salish culture to your own family or culture?

I’ve been struggling to answer this question, and the closest thing my immediate family shares with Coast Salish culture is how my father’s connection to culture was destroyed by an invading colonial power. My adopted father was born in Korea in 1924, a time when Korea was under Japanese rule, as the country of his birth had been annexed by Japan following its victories in 1905 in the Russo-Japanese War. During the Japanese occupation, Korean culture was suppressed in ways that were similar to how Indigenous First Nations and Inuit were dismantled by the colonial-settler government of Canada. For example, according to Wikipedia, Koreans:

had to give up their Emperor in 1907;

were forced to submit to a process of Japanization, wherein Japanese culture assimilates and destroys the local culture by:

renaming Korea itself, to the Japanese name Chōsen;

banning of traditional Korean names, where Koreans had to adopt Japanese naming conventions;

banning of the Korean language;

banning of Korean culture;

banning Korean history classes in schools;

teaching the Japanese culture, language, and history in schools;

saw the extraction of natural resources for the benefit and use of Japan;

Saw saw the transfer of arable land ownership from Korean to Japanese control, wherein 52.7% of all arable land was under Japanese control by 1932;

saw the mass murder of thousands of Koreans at the hands of the Japanese military;

saw hundreds of thousands of Korean men either conscripted directly into the Japanese military itself, or forced to work as slave labour for Japanese military objectives; and

saw thousands of Korean women, aged 12-17, forced to serve as “comfort women,” where they provided sexual services for Japanese military men (“Korea under Japanese rule”)

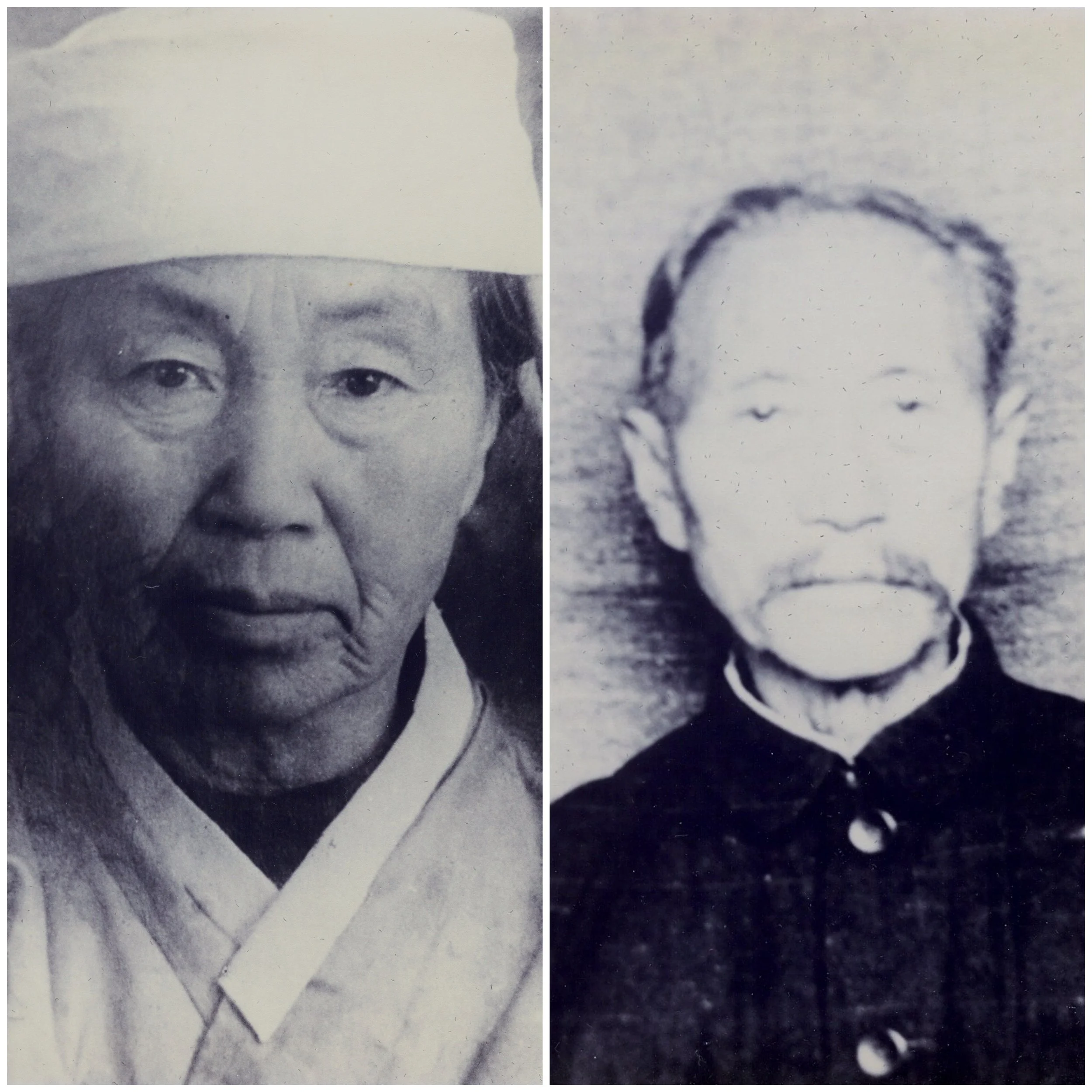

My dad rarely spoke of his youth under the Japanese occupation, which came to an end following the defeat of Japan at the end of World War 2. Today, I have two old grainy black and white photos, one of his mother, and one of his father (ITEM 3.1 below). It occurs to me I never knew their names. I’ll never know the story behind their photographs. Nor did I ever ask my Dad what they were. Cameras weren’t a ubiquitous part of society then. The photos were likely taken by someone who came to my dad’s village.

ITEM 3.1 > ANALOG PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGES > Photographer Unknown. “My Dad’s Parents.”

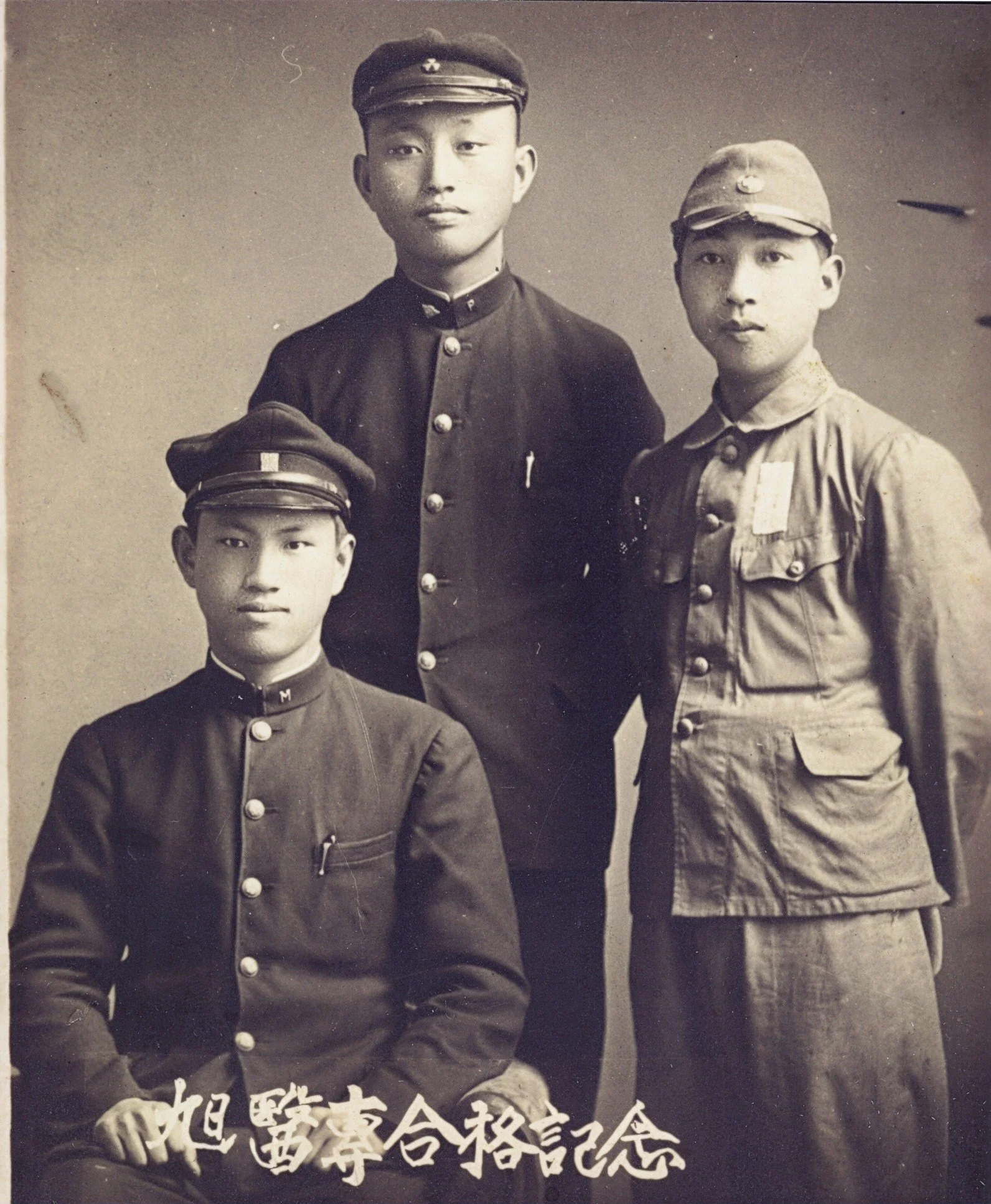

I also have an old photo of my Dad as a young man, with two other unknown individuals - possibly his siblings, possibly friends from his youth… classmates (ITEM 3.2 below). I don’t know what uniforms they were wearing. Were they school uniforms? I have heard that my Dad worked for the American military during WW2 as a translator. Was this uniform related to that? I’ll likely never know. I never asked my Dad about it.

ITEM 3.2 > ANALOG PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE > Photographer Unkown. “My Dad, Dr. Hanju Lee, seated left.”

I do know that both World War 2, as well as the internal conflicts over who would control Korea following World War 2 left his country divided and impoverished. My dad rarely spoke of this time. Nor did I ever ask my Dad about it. I know that his family’s farm was located in what became the North. In 1952, he left Korea to make a new life for himself in Canada. He first stayed at the YMCA building on Burrard Street in downtown Vancouver, and fifty-two years later, in October 2004, he would pass away a mere five blocks south in St. Paul’s Hospital, following a debilitating stroke. I know it would take forty years before those members of my dad’s family who had not been stuck in the North made contact with the surviving members still in the North.

One of the few times I ever saw him cry was when he read a letter that he’d received that told him how his younger brother, Hahn-Been Lee, had passed away early in 2004. I helped him write a short piece which was read at his brother’s funeral, but I remember him saying that with the passage of seventy years made it difficult to remember specific instances of their time together. My Dad’s strongest memories of time spent with his brother revolved around them walking to and from school in the rural countryside that they grew up in. He also remembered the times they played together on their family’s farm. It occurs to me now that I never realized that it is more than likely that his family’s farm was controlled by Japanese interests. Until I started reading about the Korea of my father’s youth this weekend, I had no idea just how deeply Japan had worked to commit cultural genocide by totally assimilating the Korean population. And he never spoke of this, and I never asked him about it.

Canada wasn’t necessarily a panacea for my dad. When he came to Canada, immigration officials misheard his name, recording it for the official record as Han Choo Lee, not Hanju Lee. When we started receiving correspondence from his family in the North, it was always addressed to Dr. Hanju Lee, and I remember my mom asking why. “Because that’s my name” my dad said. He never questioned the translation of his name, likely because my dad came from a time and place where one didn’t question the government. When I was born, I was named Steven Robert Han Lee, and as a teenager I had my name officially changed to Steven Hanju Lee, to honour the name my grandparents had given their first born son.

I know my dad had been trained as a medical doctor in Korea, but couldn’t practice when he first came to Canada. He had to take upgrading courses and exams, in German, at a university in Edmonton. I’ve heard he was told to go back to Korea, because no Korean could ever have a successful medical practice in Canada. I can’t imagine how difficult it must have been to translate medical terminology and procedures from Korean to English to German and back. I’ve heard that my dad knew seven languages at one point. As a teenager I can remember my dad laughing as he read Chinese signs in Vancouver’s Chinatown, giving me the English translation. I miss those times, those moments.

Eventually, he settled in Williams Lake, in the early to mid 1960s, where he would meet and eventually marry my mom, Beverly Jean Lee. She too had escaped the place of her birth, Vancouver, albeit for different reasons. For her, she was escaping an abusive home, one that scared her and her brothers deeply. So, growing up, I didn’t really have connection to the families my parents came from. Being Caucasian from a family with European colonial-settler roots, my mom didn’t speak Korean, so I grew up in a household where it was just the three of us, shaping our own future together. It would be many years later that I would learn that they had met during a time that anti-miscegenation laws were still on the books in many places - laws that enforced racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships. I remember my mom talking to me about the hate they experienced when they travelled, and it’s something I still have a chance to ask my mom about, because she’s still here.

I remember my dad turning to alcohol to deal with some of his problems. With the racism, the isolation. But only now, after suffering from my own major depression, anxiety, and self-isolation am I able to empathize with the feelings he must have been trying to bury. Every night, like clockwork, he would fill a glass with ice, opening a bottle of Canadian whisky, letting the warm, brown liquid fill the glass up to the rim. He’d usually have this with food, reheating leftovers from dinner in the microwave, sitting down to consume this while watching Lloyd Robertson host the CTV National News. Some nights would end with my parents at each other’s throats, shouting, screaming, and even getting physically violent with one another. Other nights would end with my dad stumbling to bed, or simply passing out on the couch. He never let the drink interfere with his work though, he’d always be up early the next day, off to the hospital to do rounds, surgeries, and hours at his family practice.

When he retired, his interest switched from medicine to studying the stock market, where he’d be up early to read the Globe & Mail religiously, with various tv-shows talking business and the stock market on in the background. He was very good at picking winners, and I remember one broker asking my dad in awe, “how do you know all this stuff?” It’s something he just did, and it’s something I never really asked my dad about. At one point in 2002, his interest in the markets stopped as dementia set in. Age 78. My mom has always quipped that my dad never really got a chance to truly enjoy retirement because he was always driven to work hard. Which isn’t a bad thing, as I do believe his interest in the markets kept his mind young. I realize now that it was also likely part of a distraction that helped him get past having to remember his youth. Something I never asked him about.

What is different or something you find fascinating about Coast Salish culture, and why?

I’ve always found the Coast Salish culture’s connection to nature and spirituality to be fascinating. In reading Richard Wagamese’s book, One Story, One Song, many passages stood out for me, but one in particular captured the essence of ITEM 3.3, Len Pierre’s slide from this week’s lecture focussing on the spirituality and faith of the Coast Salish People - as well as a worldview I aspire to uphold. Specifically, Wagamese notes:

“We are one spirit, one song, and our world will be harmonious only when we make the time to care. For ourselves. For each other. For our home. You don’t need to be a Native person to understand that - just human” (37).

ITEM 3.3 > SLIDE > Len Pierre Consulting. “Faith of the Coast Salish People.”

Growing up, my family didn’t have deep ties to religion. Technically, I was raised as a Christian, having first been baptized at the Cariboo Bethel Church, sometime before the age of 9, and again at the White Rock Christian Fellowship & Academy at 13 or 14. But we didn’t attend Sunday services with any kind of regularity, especially in the summers when my parents would take me to a small cabin they had just out of town, on Felker Lake. As such, nature was more of a spiritual escape for me growing up in Williams Lake. I remember spending hours wandering around two small wooded areas that stood on the edge of my family’s property, recreating the scenes that took place on the forest moon of Endor from THE RETURN OF THE JEDI. I remember going for walks with my Dad, along trails that were across the gravel dirt road from our property, reaching into the woods, trails etched out by teenagers on ATVs. I was never allowed to explore these areas on my own, as the threat of encountering wild animals such as bears, always loomed over the space. I remember swimming with my parents, and with kids from neighbouring properties. I remember sitting in the small living room of our cabin, watching summer storms and lightening flashing across the lake itself. Echoing thunder a few moments later. My monkey mind, which has become very good at beating myself up, would tell you that I took my life as a child in Williams Lake for granted. But I didn’t know anything else. It felt profoundly peaceful, and safe to be living in a small town, carved into a valley by a lake surrounded by the forested woods of the Cariboo mountainscape. Whenever I was out in nature, surrounded by a never ending thicket of trees, I remember feeling so small as I’d look up at the sky peaking through the canopy of dark, hunter green. It’s a feeling I still have today whenever I walk through a forest or any kind of thicketed area. A feeling or being small, but connected nonetheless to the beauty that surrounds me. Small, but protected too by the nature that surrounds me.

As a teenager, I remember reading a book called THE SEAT OF THE SOUL by Gary Zukav and it’s a book that would profoundly influence me and the kind of person I wanted to be like. At its most basic essence, Zukav speaks to the qualities of living with harmony, cooperation, sharing, and having reverence for all life, no matter what. In January 2020, when I was sick with what I’m certain was probably COVID, I re-read SEAT OF THE SOUL for the first time in twenty years, and I watched countless YouTube videos where Zukav spoke. The idea of blessing everyone you meet also stood out for me. And I’ve expanded the basic essence into a kind of mantra I try to actualize in my own life - and that is, to live life with:

…unconditional compassion, cooperation, curiosity, empathy, forgiveness, friendship, gratitude, harmony, sharing, love, and reverence for all life, starting with ourselves, no matter what.

I put that as a quote, so that it will stand out, but it’s not something you’d find verbatim in any text, as it’s something I’ve expanded on and added to over the last few years. A lot of ideas that Zukav speaks to seem rooted in Eastern Philosophy, such as Buddhism - as well as in the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction programs as developed in the 1970s by Jon-Kabat Zinn.

And like Indigenous First Nations film critic Jesse Wente, the movie theatre would also become a kind of sanctuary for me.

WEEK 03 WORKS CITED

“Korea under Japanese rule.” Wikipedia. Wikipedia Foundation, 08 Jan 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korea_under_Japanese_rule.

This week’s assignment can also be viewed in PDF format.