Transformative Territorial Acknowledgment Presentation

Contributions to the Learning Community Self-Evaluation

Transformative Territorial Acknowledgment Presentation

Contributions to the Learning Community Self-Evaluation

Over the duration of this course, I also completed the following workshops online…

Canadian Indigenous History & Cultural Sensitivity - “A comprehensive course on Canadian Indigenous relations, cultural practices, and the historical impact of colonization.”

Artifact 01 > Lee, Steven. “Certificate of Completion - Canadian Indigenous History & Cultural Sensitivity.” Udemy, 28 Oct 2023.

Artifact 02 > Lee, Steven. “Certificate of Completion - Indigenous Awareness - Self-Guided Training.”

Artifact 03 > Lee, Steven. “Certificate of Completion - Indigenous Relations - Self-Guided Training.”

FIGURE 1 > VIDEO > Len Pierre Consulting. “Indigenous Cultural Appropriation vs Appreciation with Melissa McIntyre.” YouTube, 15 Feb 2023.

FIGURE 1 > VIDEO > TEDx Talks. “A Beginner’s Guide to Decolinization | Kevin Lamoureux | TEDxSurrey.” YouTube, 20 Apr 2022.

FIGURE 2 > VIDEO > TEDx Talks. “Decolonization is for Everyone | Nikki Sanchez | TEDxSFU.” YouTube, 12 Mar 2019.

After reviewing the 94 Calls to Action, choose one of the actions items and provide a brief reflection on the action item:

What did you learn?

How does this make you feel?

What did it make you think of?

Has this action item been completed since 2015?

Jesse Wente, in his 2021 memoir, UNRECONCILED: FAMILY, TRUTH, AND INDIGENOUS RESISTANCE describes how the Truth and Reconciliation Commission provided a watershed opportunity for Indigenous Peoples to authentically share the trauma they experienced because of the Residential School system, but noted how:

“And from that bravery came the TRC’s ninety-four calls to action, meant to honour those stories and the people who lived them as well as all those who were never afforded the chance to tell their own. Taken together, these steps offer a path to reconciliation that is paint-by-numbers easy to wrap your head around: start at number one, proceed to ninety-four, and boom, there you have it—reconciled. But that apparent ease hasn’t translated to implementation or action. More than half a decade since the report’s release, only a scant few of the calls have been addressed, by even the most generous of interpretations. Some would say that the true number is zero” (Wente 188).

See this document for guidelines on how to construct a reflective writing assignment.

Objective: What is this quote or idea about? What caught your attention?

Reflective/Reaction: Why did you choose this quote or idea? How do you identify with it?

Interpretive: What does it mean to you? What insights did you get from the quote or idea? How has your thinking changed by reflecting on this quote or idea? What research can support or challenge your thinking.

Decisional: How can this new or enhanced interpretation be applied to your professional practice?

ITEM 7.1 > IMAGE > Ontario Arts Protocols. “Indigenous Arts Protocols.” YouTube, 23 Oct 2016.

ITEM 7.2 > VIDEO > SBS Dateline. “In Canada, tourist shops are flooded with fake Indigenous art | SBS Datine.” YouTube, 4 Jun 2023.

See this document for guidelines on how to construct a reflective writing assignment.

Objective: What is this quote or idea about? What caught your attention?

Reflective/Reaction: Why did you choose this quote or idea? How do you identify with it?

Interpretive: What does it mean to you? What insights did you get from the quote or idea? How has your thinking changed by reflecting on this quote or idea? What research can support or challenge your thinking.

Decisional: How can this new or enhanced interpretation be applied to your professional practice?

My perspective on colonial Canada has largely remained the same, as I’ve been familiar with the negative impacts of colonialism for a long time.

Specifically, Margaret Kohn and Kavita Reddy, in their article about colonialism for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines colonialism as “…a practice of domination, which involves the subjugation of one people to another” (Kohn).

Kohn, Margaret and Kavita Reddy, "Colonialism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/colonialism/#:~:text=Colonialism%20is%20a%20practice%20of,criticize%20and%20justify%20European%20domination.

See this document - TRANSFORMATIVE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT GUIDE.

And watch the following videos…

ITEM 4.1 > VIDEO > Len Pierre Consulting. “Transformative Territory Acknowledgements Webinar.” YouTube, 01 Feb 2023.

ITEM 4.2 > VIDEO > Fraser Health. “Territory Acknowledgment Protocol.” YouTube, 15 Jun 2020.

See this document for guidelines on how to construct a reflective writing assignment.

Objective: What is this quote or idea about? What caught your attention?

Reflective/Reaction: Why did you choose this quote or idea? How do you identify with it?

Interpretive: What does it mean to you? What insights did you get from the quote or idea? How has your thinking changed by reflecting on this quote or idea? What research can support or challenge your thinking.

Decisional: How can this new or enhanced interpretation be applied to your professional practice?

I’ve been struggling to answer this question, and the closest thing my immediate family shares with Coast Salish culture is how my father’s connection to culture was destroyed by an invading colonial power. My adopted father was born in Korea in 1924, a time when Korea was under Japanese rule, as the country of his birth had been annexed by Japan following its victories in 1905 in the Russo-Japanese War. During the Japanese occupation, Korean culture was suppressed in ways that were similar to how Indigenous First Nations and Inuit were dismantled by the colonial-settler government of Canada. For example, according to Wikipedia, Koreans:

had to give up their Emperor in 1907;

were forced to submit to a process of Japanization, wherein Japanese culture assimilates and destroys the local culture by:

renaming Korea itself, to the Japanese name Chōsen;

banning of traditional Korean names, where Koreans had to adopt Japanese naming conventions;

banning of the Korean language;

banning of Korean culture;

banning Korean history classes in schools;

teaching the Japanese culture, language, and history in schools;

saw the extraction of natural resources for the benefit and use of Japan;

Saw saw the transfer of arable land ownership from Korean to Japanese control, wherein 52.7% of all arable land was under Japanese control by 1932;

saw the mass murder of thousands of Koreans at the hands of the Japanese military;

saw hundreds of thousands of Korean men either conscripted directly into the Japanese military itself, or forced to work as slave labour for Japanese military objectives; and

saw thousands of Korean women, aged 12-17, forced to serve as “comfort women,” where they provided sexual services for Japanese military men (“Korea under Japanese rule”)

My dad rarely spoke of his youth under the Japanese occupation, which came to an end following the defeat of Japan at the end of World War 2. Today, I have two old grainy black and white photos, one of his mother, and one of his father (ITEM 3.1 below). It occurs to me I never knew their names. I’ll never know the story behind their photographs. Nor did I ever ask my Dad what they were. Cameras weren’t a ubiquitous part of society then. The photos were likely taken by someone who came to my dad’s village.

ITEM 3.1 > ANALOG PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGES > Photographer Unknown. “My Dad’s Parents.”

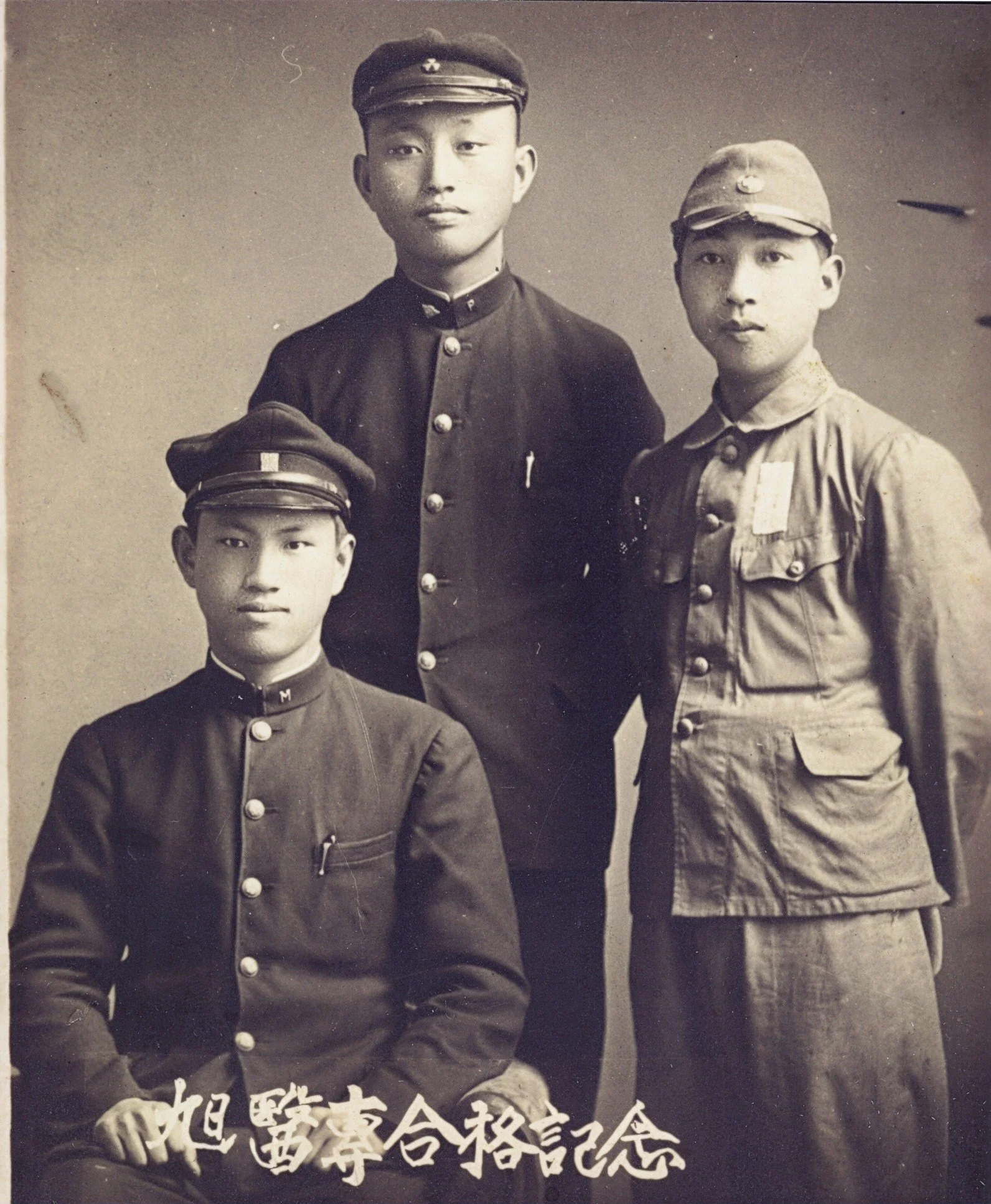

I also have an old photo of my Dad as a young man, with two other unknown individuals - possibly his siblings, possibly friends from his youth… classmates (ITEM 3.2 below). I don’t know what uniforms they were wearing. Were they school uniforms? I have heard that my Dad worked for the American military during WW2 as a translator. Was this uniform related to that? I’ll likely never know. I never asked my Dad about it.

ITEM 3.2 > ANALOG PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE > Photographer Unkown. “My Dad, Dr. Hanju Lee, seated left.”

I do know that both World War 2, as well as the internal conflicts over who would control Korea following World War 2 left his country divided and impoverished. My dad rarely spoke of this time. Nor did I ever ask my Dad about it. I know that his family’s farm was located in what became the North. In 1952, he left Korea to make a new life for himself in Canada. He first stayed at the YMCA building on Burrard Street in downtown Vancouver, and fifty-two years later, in October 2004, he would pass away a mere five blocks south in St. Paul’s Hospital, following a debilitating stroke. I know it would take forty years before those members of my dad’s family who had not been stuck in the North made contact with the surviving members still in the North.

One of the few times I ever saw him cry was when he read a letter that he’d received that told him how his younger brother, Hahn-Been Lee, had passed away early in 2004. I helped him write a short piece which was read at his brother’s funeral, but I remember him saying that with the passage of seventy years made it difficult to remember specific instances of their time together. My Dad’s strongest memories of time spent with his brother revolved around them walking to and from school in the rural countryside that they grew up in. He also remembered the times they played together on their family’s farm. It occurs to me now that I never realized that it is more than likely that his family’s farm was controlled by Japanese interests. Until I started reading about the Korea of my father’s youth this weekend, I had no idea just how deeply Japan had worked to commit cultural genocide by totally assimilating the Korean population. And he never spoke of this, and I never asked him about it.

Canada wasn’t necessarily a panacea for my dad. When he came to Canada, immigration officials misheard his name, recording it for the official record as Han Choo Lee, not Hanju Lee. When we started receiving correspondence from his family in the North, it was always addressed to Dr. Hanju Lee, and I remember my mom asking why. “Because that’s my name” my dad said. He never questioned the translation of his name, likely because my dad came from a time and place where one didn’t question the government. When I was born, I was named Steven Robert Han Lee, and as a teenager I had my name officially changed to Steven Hanju Lee, to honour the name my grandparents had given their first born son.

I know my dad had been trained as a medical doctor in Korea, but couldn’t practice when he first came to Canada. He had to take upgrading courses and exams, in German, at a university in Edmonton. I’ve heard he was told to go back to Korea, because no Korean could ever have a successful medical practice in Canada. I can’t imagine how difficult it must have been to translate medical terminology and procedures from Korean to English to German and back. I’ve heard that my dad knew seven languages at one point. As a teenager I can remember my dad laughing as he read Chinese signs in Vancouver’s Chinatown, giving me the English translation. I miss those times, those moments.

Eventually, he settled in Williams Lake, in the early to mid 1960s, where he would meet and eventually marry my mom, Beverly Jean Lee. She too had escaped the place of her birth, Vancouver, albeit for different reasons. For her, she was escaping an abusive home, one that scared her and her brothers deeply. So, growing up, I didn’t really have connection to the families my parents came from. Being Caucasian from a family with European colonial-settler roots, my mom didn’t speak Korean, so I grew up in a household where it was just the three of us, shaping our own future together. It would be many years later that I would learn that they had met during a time that anti-miscegenation laws were still on the books in many places - laws that enforced racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships. I remember my mom talking to me about the hate they experienced when they travelled, and it’s something I still have a chance to ask my mom about, because she’s still here.

I remember my dad turning to alcohol to deal with some of his problems. With the racism, the isolation. But only now, after suffering from my own major depression, anxiety, and self-isolation am I able to empathize with the feelings he must have been trying to bury. Every night, like clockwork, he would fill a glass with ice, opening a bottle of Canadian whisky, letting the warm, brown liquid fill the glass up to the rim. He’d usually have this with food, reheating leftovers from dinner in the microwave, sitting down to consume this while watching Lloyd Robertson host the CTV National News. Some nights would end with my parents at each other’s throats, shouting, screaming, and even getting physically violent with one another. Other nights would end with my dad stumbling to bed, or simply passing out on the couch. He never let the drink interfere with his work though, he’d always be up early the next day, off to the hospital to do rounds, surgeries, and hours at his family practice.

When he retired, his interest switched from medicine to studying the stock market, where he’d be up early to read the Globe & Mail religiously, with various tv-shows talking business and the stock market on in the background. He was very good at picking winners, and I remember one broker asking my dad in awe, “how do you know all this stuff?” It’s something he just did, and it’s something I never really asked my dad about. At one point in 2002, his interest in the markets stopped as dementia set in. Age 78. My mom has always quipped that my dad never really got a chance to truly enjoy retirement because he was always driven to work hard. Which isn’t a bad thing, as I do believe his interest in the markets kept his mind young. I realize now that it was also likely part of a distraction that helped him get past having to remember his youth. Something I never asked him about.

I’ve always found the Coast Salish culture’s connection to nature and spirituality to be fascinating. In reading Richard Wagamese’s book, One Story, One Song, many passages stood out for me, but one in particular captured the essence of ITEM 3.3, Len Pierre’s slide from this week’s lecture focussing on the spirituality and faith of the Coast Salish People - as well as a worldview I aspire to uphold. Specifically, Wagamese notes:

“We are one spirit, one song, and our world will be harmonious only when we make the time to care. For ourselves. For each other. For our home. You don’t need to be a Native person to understand that - just human” (37).

ITEM 3.3 > SLIDE > Len Pierre Consulting. “Faith of the Coast Salish People.”

Growing up, my family didn’t have deep ties to religion. Technically, I was raised as a Christian, having first been baptized at the Cariboo Bethel Church, sometime before the age of 9, and again at the White Rock Christian Fellowship & Academy at 13 or 14. But we didn’t attend Sunday services with any kind of regularity, especially in the summers when my parents would take me to a small cabin they had just out of town, on Felker Lake. As such, nature was more of a spiritual escape for me growing up in Williams Lake. I remember spending hours wandering around two small wooded areas that stood on the edge of my family’s property, recreating the scenes that took place on the forest moon of Endor from THE RETURN OF THE JEDI. I remember going for walks with my Dad, along trails that were across the gravel dirt road from our property, reaching into the woods, trails etched out by teenagers on ATVs. I was never allowed to explore these areas on my own, as the threat of encountering wild animals such as bears, always loomed over the space. I remember swimming with my parents, and with kids from neighbouring properties. I remember sitting in the small living room of our cabin, watching summer storms and lightening flashing across the lake itself. Echoing thunder a few moments later. My monkey mind, which has become very good at beating myself up, would tell you that I took my life as a child in Williams Lake for granted. But I didn’t know anything else. It felt profoundly peaceful, and safe to be living in a small town, carved into a valley by a lake surrounded by the forested woods of the Cariboo mountainscape. Whenever I was out in nature, surrounded by a never ending thicket of trees, I remember feeling so small as I’d look up at the sky peaking through the canopy of dark, hunter green. It’s a feeling I still have today whenever I walk through a forest or any kind of thicketed area. A feeling or being small, but connected nonetheless to the beauty that surrounds me. Small, but protected too by the nature that surrounds me.

ITEM 3.4 > PHOTO > Steven H Lee, “September 18, 2023: Delta Watershed Park walk.”

As a teenager, I remember reading a book called THE SEAT OF THE SOUL by Gary Zukav and it’s a book that would profoundly influence me and the kind of person I wanted to be like. At its most basic essence, Zukav speaks to the qualities of living with harmony, cooperation, sharing, and having reverence for all life, no matter what. In January 2020, when I was sick with what I’m certain was probably COVID, I re-read SEAT OF THE SOUL for the first time in twenty years, and I watched countless YouTube videos where Zukav spoke. The idea of blessing everyone you meet also stood out for me. And I’ve expanded the basic essence into a kind of mantra I try to actualize in my own life - and that is, to live life with:

…unconditional compassion, cooperation, curiosity, empathy, forgiveness, friendship, gratitude, harmony, sharing, love, and reverence for all life, starting with ourselves, no matter what.

I put that as a quote, so that it will stand out, but it’s not something you’d find verbatim in any text, as it’s something I’ve expanded on and added to over the last few years. A lot of ideas that Zukav speaks to seem rooted in Eastern Philosophy, such as Buddhism - as well as in the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction programs as developed in the 1970s by Jon-Kabat Zinn.

And like Indigenous First Nations film critic Jesse Wente, the movie theatre would also become a kind of sanctuary for me.

“Korea under Japanese rule.” Wikipedia. Wikipedia Foundation, 08 Jan 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korea_under_Japanese_rule.

This week’s assignment can also be viewed in PDF format.

One thing I did not know was how the Métis were a distinct group with deep roots primarily across the three Prairie provinces. In reading about the Métis history, I discovered that the UBC Indigenous Foundations website described how the term did originally apply to those whose “…cultures and ethnic identities resulted from unions between Aboriginal and European people in what is now Canada (where the term) Métis stems from the Latin verb miscére, ‘to mix’” (Ouellet). The UBC website also described how the Canadian legal decision, R v. Powely [2003], as representing “…the First major Aboriginal Rights case concerning Métis peoples. The Powley decision resulted in ‘the Powley Test,’ which laid out a set of criteria to not only define what might constitute a Métis right, but also who is entitled to those rights” (Salomons). I also found it fascinating how the Métis Nation of Ontario website described the symbolism of the Métis flag (ITEM 2.1 below) which features a “…horizontal or infinity symbol… originally carried by French ‘half-breeds’ with pride… (Specifically) the symbol, which represents the immortality of the Nation, in the centre of a blue field, represents the joining of two cultures” (Métis Nation of Ontario). This kind of acceptance however, was something not always seen across all Nations.

In Martin Scorsese’s 2023 film, KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON, the marriage between colonial settlers and members of the Osage Nation was at times viewed with suspicion, especially by elder members of the Nation, and by elder colonial settlers. For example, the character of Lizzie (Tantoo Cardinal), expresses to her daughter Mollie (Lily Gladstone) her disappointment with how her daughters have watered down their Osage culture and heritage by inviting in evil, colonial-settler white men through marriage. Specifically, their conversion, in Osage, goes as follows:

Lizzie: Did you see the Owl?

Mollie: No.

Lizzie: When you do it’s a sign we are dying. Because… of you. You all marry white men. Our blood is getting white (Killers of the Flower Moon 00:45:05-00:45:37).

In David Grann’s 2017 non-fiction book, upon which the film is based, Grann goes into further detail, using an omniscient narrator to dive further into Lizzie’s thoughts about white European settlers, describing how:

“During Lizzie’s lifetime, the Osage had become dramatically unmoored from their traditions. Louis E. Burns, an Osage historian, wrote that after oil was discovered, the tribe had been ‘set adrift in a strange world,’ adding, ‘There was nothing familiar to clutch and stay afloat in the world of white man’s wealth’” (Grann 25).

Grann continued, noting how the Osage had been essentially crippled by the greed of colonial settlers, as:

“To some Osage, especially elders like Lizzie, oil was a cursed blessing. ‘Some day this oil will go and there will be no more fat checks every few months from the Great White Father,’ a chief of the Osage said in 1928. ‘There’ll be no fine motorcars and new clothes. Then I know my people will be happier’” (26).

A colonial-settler aunt and uncle also expressed displeasure in the film, describing their grandchildren as ‘half-breeds’ who wouldn’t have the same advantages in life due to their mixed ethnicity. In the same scene, Scorsese shifts from Lizzie and Mollie’s conversation to showcase the children born from the mixed-raced couples. Aunt Annie (Jo Harvey Allen) talks to Uncle Jim (Terry Allen) about their niece and nephew, their own relations, as both watch them play:

Aunt Annie: This one’s whiter than that one. You’d never know this one’s a half-breed, would you?

Uncle Jim: They’re both a couple of little half-assed savages, as far as I’m concerned.

Aunt Annie: Bless their little hearts, now, they can’t help it.

Uncle Jim: One dark, and one light. It’s like an eclipse. The Lord put his hand over the Earth and made it shake for nothing (Killers of the Flower Moon 00:45:57-00:46:29).

In Grann’s book, the thoughts of the aunt are described to us by an omniscient narrator who reveals how:

One of Ernest’s aunts, who spewed racist notions about Indians, was also visiting, and the last thing Mollie needed was for Anna to stir up the old goat” (Grann 11).

And:

“Meanwhile, Ernest’s aunt was muttering, loud enough for all to hear, about how mortified she was that her nephew had married a redskin” (12).

Finally, Eastern Woodland Métis Nation website also describes a time when the Métis had been separated from their heritage, conveying how:

“The Métis infinity flag was temporarily forgotten, and remembered only in oral tradition. With the rebirth of Métis pride and consciousness the flag was brought back” (Eastern Woodland Métis Nation).

ITEM 2.1 > IMAGE > The Métis Flag.

For me, the deep roots that Métis maintained as a result of their diversity, as compared to the divisions seen by the diversity in the Osage, ties back to the ideal of Harmony, a concept Ojibwe author Richard Wagamese, in his book, ONE STORY, ONE SONG, teaches as being:

“According to the teachings of my people… (one of) the most difficult things to achieve in life… (but) in the Aboriginal way of seeing the world, everyone is divine. Everything exists in a never-ending state of relationship. If there is order to be found, it lies in the all-encompassing faith in this belief” (Wagamese 35).

In ONE DRUM, STORIES AND CEREMONIES FOR A PLANET, Wagamese further relays how:

“The spiritual blessing of respect is harmony and the spiritual byproduct is community… It starts with the recognition that all things exist on the Sacred Breath of Creation, and that because of that we are all related, all kin, all essential to the ongoing energy, the eternal heartbeat, the one song on the one drum that is the story of our time here” (Wagamese 181).

In short, I found Wagamese’s reminder to be nothing less than deeply profound, and a reminder about the importance of community and the idea that everyone and everything is connected.

According to his website, author and educator Bob Joseph is an Indigenous leader “…in the Gayaxala (Thunderbird) clan, the first clan of the Gwawa’enuxu, one of the first tribes that make up the Kwakwaka’wakw” (Indigenous Corporate Training). Joseph has been an Indigenous relations trainer since 1994. For his blog in 2015, Joseph wrote an article that explored the lesser known aspects of the Indian Act called, 21 THINGS YOU MAY NOT KNOW ABOUT THE INDIAN ACT. In 2016, the article was reworked for print media, appearing on site, such as CBC News. And in 2018, the article Had been expanded even further into a nonfiction book of the same name. Each iteration of Joseph’s work have been well received, and circulated widely. All iterations were a response to what Joseph described in the introduction to the book as representing a “…gap in knowledge regarding the history of Indigenous Peoples that spans from Confederation in 1867 to the 1960s.” (Joseph 10). Joseph also described his goals for the ongoing project these writings represented, which included how “… Non-Indigenous Canadians be aware of how deeply the Indian act penetrated, Controlled, and continues to control, most aspects of the lives of First Nations” (10). In short, Joseph explained how “…as an Indigenous Person I look for opportunities to build bridges of reconciliation by providing information about Indigenous Peoples” (10).

ITEM 2.2 > VIDEO > Bob Joseph. “21 Things You Didn’t Know About the Indian Act Presentation.” YouTube, 23 Jul 2018.

One aspect of the Indian Act I’ve been familiar with is how it has existed since the beginning of Canadian Confederation, which Wikipedia describes as:

“…the process by which three British North American provinces—the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick—were united into one federation called the Dominion of Canada, on July 1, 1867. Upon Confederation, Canada consisted of four provinces: Ontarioand Quebec, which had been split out from the Province of Canada, and the provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Over the years since Confederation, Canada has seen numerous territorial changes and expansions, resulting in the current number of ten provinces and three territories” (“Canadian Confederation”).

One thing I didn’t know however, was how the Act is actually older than Canada itself. Specifically, Joseph notes how the:

The roots of the Indian Act lie in the Bagot Report of 1844 that recommended that control over Indian matters be centralized, that the children be sent to boarding schools away from the influence of their communities and culture, that the Indians be encouraged to assume the European concept of free enterprise, and that land be individually owned under an Indian land registry system in which they could sell to each other but not to non-Indians. The Bagot Report provided the framework for the Indian Act, 1876 (Joseph 13).

I also understood how the Act was created to manage the relationship between the Crown, the Government of Canada, and the Indigenous First Nations and Inuit upon whose land Canada now stood. I also knew how the Act treated Indigenous First Nations Peoples as children, where, as Joseph notes, the Canadian Department of the Interior in 1876 explained how: “Our Indian legislation generally rests on the principle, that the aborigines are to be kept in a condition of tutelage and treated as wards or children of the State...” (13). I also understood how the Act continuously restricted the rights of Indigenous First Nations Peoples over time. To this end, Joseph notes how:

“..,that paternalistic attitude gave way to increasingly punitive rules, prohibitions, and regulations that dehumanized Indians. By the 1920s, Indian policy took on a much darker tone. Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, wrote: “I want to get rid of the Indian problem... Our objective is to continue until there is not an Indian that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department...” (13).

I have to admit that I wasn’t totally clear on how the elected chief and band council system was entrenched in the Indian Act, having nothing to do with the various systems of governance that each nation had. Joseph notes that this new system under the Indian Act mirrored:

“…municipal-style government in which a leader and council members are elected, based on the terms and conditions of the government. The role of the elected chief is to administer the Indian Act, and in no meaningful way does this reflect their former self-government” (19).

Joseph also makes clear that this:

“…dismissal of Indigenous forms of government in favour of the European-style municipal government displaced traditional political structures and did not reflect, consider, or honour Indigenous needs and values” (19).

In browsing YouTube, I was impressed at how much discussion has been generated by Joseph’s work. One Pastor in Guelph, Ontario, even did a series of video discussions about the book, which he encouraged all his parishioners to read. ITEM 2.3 features one of those discussions, in which the Pastor introduces Joseph’s book.

ITEM 2.3 > VIDEO > St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Guelph. “Introduction to the 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act.” YouTube, 29 Sep 2022.

“Canadian Confederation.” Wikipedia, Wikipedia Foundation, 12 Dec 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Confederation.

Eastern Woodland Métis Nation. “The Métis Flag.” 2023. https://easternwoodlandmetisnation.ca/the-metis-flag/. Accessed 14 Sep 2023.

Grann, David. “Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI.” Kindle ed., Doubleday, 2017.

Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. “Bob Joseph: Founder & President.” 2023. https://www.ictinc.ca/ict-team/bob-joseph. Accessed 14 Sep 2023.

Joseph, Bob. “21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality.” Kindle ed., Indigenous Relations Press, 2018.

Killers of the Flower Moon. Directed by Martin Scorsese, Apple Studios / Imperative Entertainment / Sikelia Productions / Appian Way Productions, 2023.

Métis Nation of Ontario. “Symbols and Traditions.” Métis Nations of Ontario. https://www.metisnation.org/culture-heritage/symbols-and-traditions/#:~:text=Métis%20Flag,the%20joining%20of%20two%20cultures.. Accessed 14 Sep 2023.

Oullet, Rick, and Erin Hansen. “Métis.” Indigenous Foundations UBC, 2009. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/metis/. Accessed 14 Sep 2023.

Salomons, Tanisha, and Erin Hanson. “Powley Case.” Indigenous Foudations UBC, 2009. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/powley_case/. Accessed 14 Sep 2023.

Wagamese, Richard. “One Drum: Stories and Ceremonies for a Planet.” Douglas & McIntyre Ltd., 2019.

Wagamese, Richard. “One Story, One Song.” Douglas & McIntyre Ltd., 2011.

This week’s assignment can also be viewed in PDF format.

In the fall of 2023, I took INDIGENOUS STUDIES 1100: Introduction to Indigenous Studies, offered at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. My professor for the term was Len Pierre, of Len Pierre Consulting.

Figure 1.2 > VIDEO > TEDx TALKS. “Cultural Safety Education as the Blueprint for Reconciliation | Len Pierre | TEDxSFU.” YouTube, 29 Mar 2022.

This is the course syllabus.

This online journal will act as a repository of my written reflections and assignments for this course.

Please take a moment to introduce yourselves in the forum here. You can answer the following questions in your introduction:

I’m Steven Hanju Lee, but at birth I was named Steven Robert Han Lee. As a teenager, I changed my name to Steven Hanju Lee, to reflect the name of my late father. Han was his given name here in Canada, and it’s been a part of me since birth. But when he came to Canada in 1952 to escape his war torn country of birth, Korea, the Canadian customs and immigration officials misheard his name and recorded it as Han Choo Lee. He never spoke to the mistake, and it wasn’t until the early 1990s that we even knew his name was Hanju. It was at this time that he had made contact with his surviving family members who had been stuck in the North, and they corresponded regularly by mail until my Dad’s passing in 2004. But every letter that came, it was addressed to Hanju Lee, not Han Choo Lee. My Mom asked why this was the case, and my Dad responded, “Because that’s my name. I never asked my Dad why he didn’t correct them, but I assume it was because it was a very different time in the 1950s, where people, especially people of colour, didn’t question government. So upon learning this, I decided I wanted to honour the name his parents gave him, and so I became Steven Hanju Lee.

I first studied at Kwantlen University College twenty years ago, when I completed a diploma in Marketing Management, and a certificate in Business Management. At this time I ended up working for the Kwantlen Student Association, organizing events, and I ended up doing that for just over a decade. When I first started at the KSA, I helped the organization create representatives on its board for students who traditionally had trouble accessing post secondary education, and one of those positions was a First Nations Liaison alongside 4 other positions, which was later expanded to 7. My job wasn’t all events though, at one point I helped fight a group of students who took over the Association to line their pockets with student money: they literally setup schemes like shell companies to funnel money out of the million dollar organization. It was a fight that went to the Supreme Court of BC, where a court ordered election was called and the other students were given the boot. As the Association was cleaned up, it expanded by creating The Runner, and many other programs.

More recently, I came back to Kwantlen to do a Bachelor of Fine Arts, and I’m very close to finishing that. Creating art and telling stories is something I’ve always enjoyed, and I’ve played with a variety of mediums including drawing, painting, performance art, photography, and sculpture to explore themes related to the environment as well as to portrayals of the self. When it comes to portrayals of the self, I’ve tried to maintain a daily subverted selfie project on Instagram, where I don’t shy away from exploring my struggles with anxiety, diabetes, high blood pressure, and major depressive disorder. This year, I also had a stroke on January 31 which left me hospitalized for a chunk of February. I find so many people on social media do their best to curate their lives as being perfect, when in reality, no one’s life is perfect. We all have our flaws and struggles, and it should be okay to share that.

I was born in Williams Lake, and my family lived there for the first 12 years of my life. I mentioned my father was Korean, and he married a Caucasian Canadian woman, my mother, at a time when interracial relationships and marriages were still illegal in many parts of the United States. They eventually tried to have children, but couldn’t conceive - so they adopted me, before I was even born. I’m grateful for them doing that, and for the life they gave me.

I know who my biological Mother was, although I never met her. I did recently make contact with a half-sister, who has been incredibly kind and supportive. I know my birth Mother’s lineage traces back to a William Pinchbeck, a colonial settler who took as his wife, the daughter of Chief Will’ium, Chulminick. The city of Williams Lake is actually named after Chief Will’ium, my Great, Great, Great Grandfather. According to their website, “The Williams Lake First Nation (WLFN), or the T’exelcemc (people of WLFN) have belonged to the Secwepemc (or Shuswap) Nation for over 6500 years” (Williams Lake First Nation), and this week the federal government of Canada formally apologized to them for the lands that were taken from them. It’s always bothered me to a degree that I probably shouldn’t exist - that my life comes from a series of events wherein my Great, Great, Great Grandmother was likely forced into her marriage by a stranger from a far away land who just took her for himself.

I don’t really talk about this much. A few years ago I took the IDEA class on myth, and one project we did involved researching our ancestry - so I traced back the lives of both my biological Mother and my adopted parents (I have no knowledge about my biological Father, as I was the product of an affair). I don’t speak to my biological lineage publicly, as I wasn’t raised within the WLFNs community. I’m also fairly removed from my ancestors, by three generations. In regards to this, I’m aware of situations such as one’s representative of US Senator Elizabeth Warren, who claimed to have First Nations ancestry, although it turned out she was 6-10 generations removed, and she was criticized for it. Had it turned out she had no lineage, she would have been labeled a “pretendian,” which Wikipedia describes as being “…a person who has falsely claimed Indigenous identity by claiming to be a citizen of a Native American or Indigenous Canadian tribal nation, or to be descended from Native ancestors… As a practice, being a pretendian is considered an extreme form of cultural appropriation, especially if that individual then asserts that they can represent, and speak for, communities they do not belong to” (“Pretendian”).

In the report I did for the IDEA class on mythology, I remember lamenting that even though I’m proud of my connections to European, First Nations, and Korean lineages, I also feel that I don’t really belong to any of them. My adopted Dad was the only Korean in Williams Lake, so I grew up speaking English and I never really learned much about his culture. My adopted Mother, like my Dad, had escaped a childhood horror created by some awful family members - so there was a disconnect there as well. I’m excited I’ve touched base with my half sister though, as she seems to have some connection with the WLFN, so I’m eager to learn more about that aspect of my life in the future.

As a child, I remember our elementary school took us to visit the Alkali Lake First Nations. know they are a people who have suffered many heartbreaking injustices. There was discussion about how many members were struggling to overcome addiction, and the abuses suffered at residential schools. I thought about that a lot recently, having read the novel by Richard Wagamese, and seen the feature film that was made from it, INDIAN HORSE, in one or Dr Paul Tyndall’s English courses on film studies here at Kwantlen. It’s executive produced by Clint Eastwood, who himself is a Republican Conservative, so I like to encourage people online to watch, those who deny that injustices took place at the residential schools. It’s usually people who are conservative who deny it, which is why I like to emphasize Eastwood’s involvement (another film I encourage them to watch is RABBIT PROOF FENCE, as it shows how these injustices took place across the globe).

In University, I’ve had several classes with some amazing students who are from local First Nations. Roxanne Charles, finished her fine arts degree with a minor in anthropology and she’s become a very close friend, who I’ve also been fortunate enough to show artwork with. She’s a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores many of the injustices First Nations have faced. She works hard at building bridges within First Nations communities across the province. She’s also one of the kindest people I know, who works hard to maintain a positive attitude even when times are tough. I remember in a performance art course we took together she recreated the ceremony of giving thanks to the Earth and the Land before stripping part of a Cedar tree for bark used in weaving. Care and attention is taken with that process, so as not to permanently harm the trees. The reverence taken is beautiful, and something everyone should do - to give thanks, and leave the Earth a better place than you found it.

The connection to the land is something I’ve always found fascinating, the respect and reverence for it is something I’d love to learn more about. In Dr Lee Beavington’s IDEA 1100 class we read BRAIDING SWEETGRASS which touched upon this as a major theme, and it’s one that I think I’ve barely even touched the surface with.

I’d also like to learn more about countering the myths perpetuated by those on the right. For example, some argue that First Nations would war amongst and conquer each other violently before colonial settlers came.

“See, when they got off the boat, they didn’t recognize us. They said, ‘Who are you?’

And we said, ‘We’re the people. We’re the human beings.’

And they said, ‘Oh, Indians.’ Because they didn’t recognize what it meant to be a human being.”

‘I’m a human being. This is the name of my tribe. This is the name of my people, but I am a human being.’

But the predatory mentality shows up, and starts calling us Indians, and committing genocide against us as a vehicle of erasing the memory of being a human being. So, they used warped textbooks, history books, and when film came along, they used film too. You go into our own communities, how many of us are fighting to protect our own idea of being an Indian. And six hundred years ago that word ‘Indian,’ that sound was never made in this hemisphere. That sound, that noise, was never, ever made. Ever. And we’re trying to protect that as an identity. So, it affects all of us. It’s reached a point evolutionary speaking, we’re starting to not recognize ourselves as human beings. Because we’re too busy trying to protect the idea of a Native American, or an Indian. But we’re not Indians, and we’re not Native Americans. We’re older than both concepts. We’re the people. We’re the human beings.”

To help Len understand how to best support all students this course to help you be successful and get the most out of your learning, please answer the following:

Having taken several Coursera classes, I enjoy a mix of activities - from watching videos, to short readings, as well as activities that explore the ideas being discussed including creative exploration, written reflection, and even short quizzes.

In the past, my anxiety and depression have left me paralyzed, and when that happens I retreat from my responsibilities and routines. That’s been the biggest thing preventing me from learning.

I’m going to do my best not to get paralyzed this term. I did have a stroke earlier this year, but I’ve been in physiotherapy for it. I also hurt my feet in July and my right foot wasn’t healing properly, and I went to the ER on August 14. Since then I’ve been on daily antibiotics by IV as I had a bad infection. One doctor wanted to amputate some of my toes but thankfully the other doctors were willing to do wound therapy which seems to be working!

“Pretendian.” Wikipedia. Wikipedia Foundation, 08 Jan 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pretendian.

Trudell, John, interviewee. Reel Injun. Directed by Neil Diamond / Jeremiah Hayes / and Catherine Bainbridge, Rezolution Pictures / National Film Board of Canada, 2009.

Williams Lake First Nation. www.wlfn.ca. Accessed 09 Sep 2023.

This week’s assignment can also be viewed in PDF format.