WEEK 04, CHAPTER 03: Assembling Cultural Safety Strategies

WEEK 03, CHAPTER 02: Colonial Socialization and Ideology

In this week’s unit, Len Pierre introduced and presented the ideas of:

colonial socialization and ideology, largely considered to be the root cause of widespread anti‑Indigenous racism in Canada;

how media, education, family narratives and policy have normalized stereotypes (Pocahontas myth, Halloween costumes, mascots, cartoons);

colonialism is embedded institutionally — through Canada’s Indian Act legislation, residential schools, voting laws, and the 1960s White Paper — all of which contributed to and produced long‑term harm.

Pierre discusses several key historical markers, including:

the potlatch ban (~60 years);

100+ years of school narratives;

$200 bounty examples; and

voting restrictions.

Pierre’s discussion also touches on the progress and resocialization that is underway, including:

BC K–12 curriculum reform (2015);

UNDRIP adoption;

First Nations Health Authority’s hospital cultural‑safety standards; and

ongoing land‑back initiatives.

Framing Colonial Socialization

Pierre began with a reflection on Canada's global reputation based on travel or immigration experiences and noted how there is a common global perception of Canada as free, kind, respectful, and multicultural.

Pierre contrasted this with the point about how these perceptions omit a key historical context rooted in colonial socialization and ideology which form the root of anti-Indigenous racism in Canada.

Sadly, many Canadians deny the existence of systemic racism.

Understanding socialization and ideology is a key factor necesssry for addressing racism.

Media & cultural appropriation

The 1995 animated feature film POCAHONTAS became popular and widely known when it was released:

It is important to remember that Pocahontas is a real historical figure, not solely a fictional or mythical character as portrayed in films and television shows. She was abducted at age 12 and taken overseas. Pocahontas later died from disease. Ultimately Pocahontas was one of the earliest missing and murdered Indigenous women/girls.

Walt Disney presented a romanticized, glorified narrative of a horrific historical tale. The Disney film depicted Pocahontas and John Smith as lovers who nearly caused war but parted peacefully, influencing youth perceptions of history and intercultural contact.

Indigenous-themed Halloween costumes constitute cultural appropriation and public displays of cultural humiliation. In short, treating Indigenous identity as a one-night costume is disrespectful, extractive, and humiliating. In regards to this, it is also important to remember how:

Anti-potlatch legislation in the late 1800s criminalized and outlawed:

praying;

singing;

speaking Indigenous languages;

wearing traditional clothing;

Indigenous cultural practices;

Legislation prohibited Indigenous gatherings of more than six people. These physical gathering restrictions were in place for 60 years. The federal government enforced the gathering ban out of fear of cultural resurgence. Pierre compared the recent COVID-19 lockdowns of up to ~60 days (which saw restrictions on gatherings for weddings, parties, concerts, festivals, and funerals) to the 60 years of enforced cultural gathering restrictions to illustrate the harm that was caused.

In the realm of education, Breastplate and Buckskin was a Canadian history textbook used from the 1950s onward. Specifically:

The textbook depicted Indigenous peoples as devils attempting to scare the early settler Cartier; this imagery was taught in the Canadian curriculum.

Speaker referenced Justice Murray Sinclair in connection with the textbook imagery.

Cartoons, Westerns & Stereotypes

Pierre grew up in the 90s watching THE BUGS BUNNY & TWEETY SHOW on Saturday mornings. Specifically:

One episode depicted Bugs defending a fort against Indigenous Native American characters;

The Indigenous characters appeared on horseback and on foot, using bows, arrows, and tomahawks;

The background music made use of a stereotypical powwow drum; and

Bugs Bunny shot and killed Indigenous characters while singing "One little, two little... Indians" as he tallied his kills and then erasing half a tally while calling one a "half-breed.”

Pierre asked his audience to consider what messages children learn from such portrayals… In short, the cartoon portrayal taught kids that Indigenous people are dangerous, savage, heathen, or enemies of humanity/state. Bugs represented the everyday American man (cowboy hat, blue suit, rifle) as a white saviour / defender.

Early Western films also framed Indigenous people as savages.

Indigenous roles in those films were often played by white actors in red paint, not by Indigenous people.

School, family & peer socialization

Speaker referenced Justice Murray Sinclair's claim that the Canadian curriculum taught anti-Indigenous approaches.

School curriculum in the 1990s contained almost no Indigenous content.

Speaker experienced effective erasure from history books and textbooks.

Anti-Indigenous narratives originated from school culture and education.

Anti-Indigenous narratives originated from friends and family.

Speaker attended a predominantly white, middle-class high school.

Reserve Keatsy sent five students to that high school out of ~2000 students.

Speaker was in grade 10 when a peer in grade 8 used a racist slur.

Peer called the speaker "chug", a term used to mean "drunk Indian".

Speaker had never heard the term "chug" before that encounter.

Two non-Indigenous friends explained the term to the speaker, indicating lateral transmission of racist ideology.

Speaker later taught about these phenomena for a living, linking personal experience to professional work.

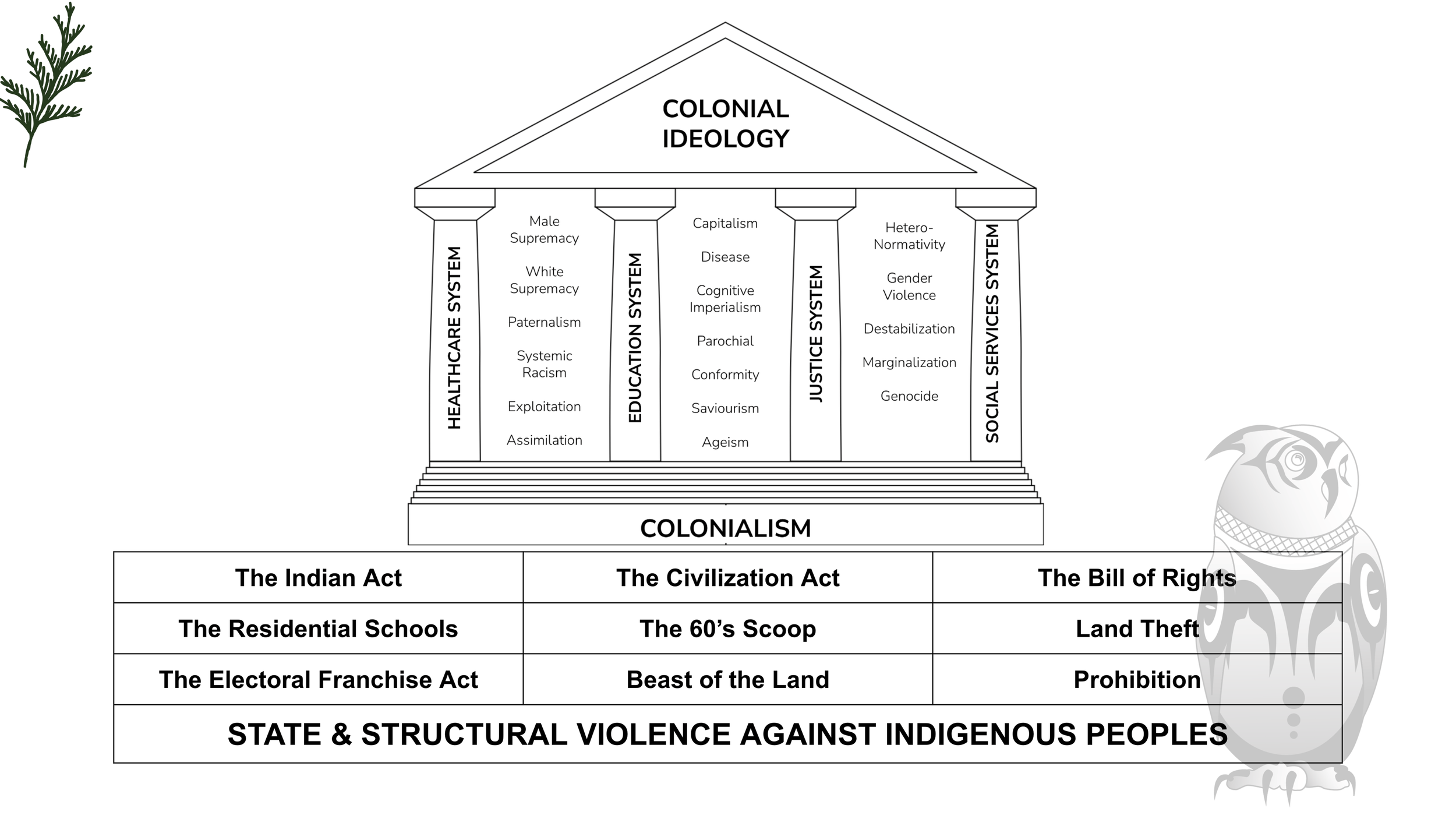

Model of colonial ideology

Colonial ideology consists of widespread beliefs interpreted as fundamental truth.

Colonial ideology frames Indigenous peoples as less deserving and less worthy.

Canada is a colonial country built on colonial ideology.

Canada would not have existed if early colonizers had respected Indigenous human rights and dignity.

Settler states share this ideology: Australia, New Zealand, United States.

Contemporary institutions retain elements and residuals of colonial ideology.

Healthcare, education, justice, and social services contain embedded colonial ideology.

Reading between the lines is necessary to identify how colonial ideology scaffolds the country.

White & male supremacy discussion

Male supremacy exists in Canada.

A woman dies from domestic violence every week in Canada (mainstream rates; Indigenous rates excluded).

Male supremacy was imported from Europe during colonization.

European societies historically positioned men as heads of household and elevated kings over queens.

Many non‑European cultures also exhibit male supremacy.

Most Indigenous nations in North America are matriarchal or matrilineal.

Matriarchal denotes women leading households and holding governance and leadership roles.

Matrilineal denotes inheritance transmitted via the mother's bloodline.

Colonizers reacted to Indigenous women's power by implementing assimilation policies.

Policy example: a First Nations woman marrying a white man lost her Indian status and Indigenous rights.

White supremacy exists in Canada and produces long‑lasting residual effects.

White supremacy is less prevalent today than in previous decades and generations.

White supremacy exists on a spectrum from overt symbols (swastikas, KKK, violent hate crimes) to subtle forms.

Subtle forms of white supremacy are central to cultural safety and transformation work.

Laws, land theft & doctrine of discovery

Boxes under a temple metaphor represent the foundation of Canada built on anti-Indigenous laws.

Examples of anti-Indigenous laws listed: Indian Act, residential schools, Electoral Franchise Act, Civilization Act, 60s Scoop, Bill of Rights.

Indian Act described as the most racist and oppressive legislation in Canada.

Residential schools were legislated; families faced jail for refusing to surrender children.

Electoral Franchise Act delayed Indigenous voting; Indigenous people were the last to receive voting rights.

Indigenous women were the last group in the country to obtain the vote.

Voting rights expanded gradually: landowning white men → some white women → Asians → Indigenous people (granted in 1960s).

Bill of Rights excluded Indigenous people because the older Indian Act took legal precedence.

Discrimination characterized by exclusion, ignoring, and labeling.

All lands in Canada described as stolen; Canada characterized as an administrative or landless state due to broken or non‑existent treaties.

Definition: 'unceded' means never surrendered; no transaction or agreement for land or territory.

Case example: James Douglas attempted a treaty system in BC, failed, and facilitated land transfers to settlers.

Settler families received 260 acres for free; First Nations received 10 acres of reserve land, often of poorest quality.

Canada's national wealth attributed to the theft of Indigenous lands and territories.

Resocialization & systemic reforms

Resocialization is in progress to address colonial ideology and colonial socialization.

The new National Day for Truth and Reconciliation has substantially changed the national landscape.

Reconciliation is intergenerational and incremental; consistency matters more than intensity.

British Columbia transformed the K–12 curriculum in 2015 to embed Indigenous culture across almost every subject.

Current K–12 students learn substantially more about Indigenous peoples than previous generations.

Curriculum changes will produce intergenerational benefits as students become future leaders.

Universities and colleges require mandatory Indigenous cultural safety training for professions working with people (social workers, teachers, nurses, doctors).

A new health standard requires every single hospital to meet standards for culturally safe care and cultural awareness.

British Columbia adopted UNDRIP and implemented a new action plan.

The First Nations Health Authority has emerged as the first organization of its kind worldwide.

Organizations and governments are committing to land back.

Assignment & closing

Write a very short reflection in a Word document and convert to PDF.

Instructor requests PDF to avoid manual downloading on their end.

Acceptable alternatives: submit a video recording, an audio file, or a photo of the written reflection.

Upload submission to the assignment portal.

Instructor will read reflections as soon as possible.

Proceed to the final chapter: Indigenous Cultural Safety, which provides tools, tips, tricks, and strategies.

CrashCourse: Socialization Summary

Introduction

The video titled "Socialization" explores the intricate processes through which individuals learn and internalize the values, beliefs, and behaviours of their society. It emphasizes that socialization is a lifelong process involving various agents, including family, peers, schools, media, and institutions. The episode seeks to answer the question of "who" socializes individuals and outlines the different contexts and types of socialization.

The Concept of Socialization

Socialization is defined as the process by which individuals develop their personalities and human potential while learning about their society and culture. This ongoing process begins in early childhood and continues throughout life, influencing how individuals act and what they value.

Key Agents of Socialization

**Family**: The primary and most significant agent of socialization, where initial experiences with language, values, behaviors, and norms occur.

**Schools**: Act as secondary agents introducing children to broader societal rules and norms.

**Peer Groups**: Significantly influence behavior, especially during adolescence.

**Media**: An evolving force in socialization, shaping attitudes and beliefs.

**Total Institutions**: Places like the military and prisons that enforce strict behavioral norms.

---

## Family as the Primary Source of Socialization

### Primary Socialization

The family is the first environment where children learn basic skills and social norms. Parents and guardians play a critical role in teaching everything from everyday tasks to complex societal concepts.

### Cultural Capital

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's concept of "cultural capital" is introduced, highlighting how the family environment equips children with non-financial assets for future success. For example, reading habits established in childhood positively correlate with academic performance.

### Gender, Race, and Class Socialization

- **Gender Socialization**: Begins at birth with gendered names and clothing. Parents shape children’s understanding of gender roles.

- **Race Socialization**: Teaches behaviors and attitudes related to racial identity and influences views on other races.

- **Class Socialization**: Instills norms and values based on socioeconomic status, contributing to educational and occupational disparities.

### Anticipatory Socialization

This concept refers to the process where individuals learn and adopt the values and standards of groups they aspire to join, particularly seen in children mimicking adult behaviors.

---

## Secondary Socialization in Schools

### Introduction to Bureaucratic Structures

Schools introduce children to formal rules and bureaucratic systems beyond the familial context. They provide an essential framework for understanding social structures.

### Hidden Curriculum

Schools impart not only academic knowledge but also social norms and values through a "hidden curriculum." Examples include:

- **Competitiveness**: Events like spelling bees teach children the significance of winning and losing.

- **Diversity Exposure**: Schools serve as melting pots where children encounter various backgrounds, enhancing social awareness and understanding of different social issues.

---

## Peer Groups: The Adolescence Influence

### Peer Group Dynamics

Peer groups, defined as social groups sharing common interests and age, become increasingly influential during adolescence. James Coleman's study in the 1950s categorized teenage social groups into:

- **Nerds**

- **Jocks**

- **Leading Crowd**

- **Burnouts**

Coleman discovered that socialization within these groups significantly impacted educational outcomes. Peer groups can shape behaviors, leading students to adopt the norms and values of their social circle, even if they differ from their inherent traits.

### Social Prescriptions

Coleman's research indicated that group membership came with specific expectations, determining social dynamics and affecting academic performance. For instance, in schools where good grades were valued, academically inclined students thrived, while the opposite was true in environments where academic success was not socially rewarded.

---

## Media as a Modern Agent of Socialization

### Influence of Media

The video discusses how media consumption, including television and the internet, plays a significant role in contemporary socialization. Factors like class, race, and age shape media consumption patterns.

### Impacts on Attitudes

Research has revealed that exposure to media influences attitudes and social values:

- **Sesame Street**: Demonstrated positive effects on children's attitudes toward diversity.

- **MTV’s “16 and Pregnant”**: Served to alter teenage perceptions about pregnancy and contributed to declining teen pregnancy rates.

### Social Disparities

The video notes that different demographics engage with media differently, with lower-income individuals often consuming more television than higher-income groups, thereby affecting socialization experiences.

---

## Total Institutions and Resocialization

### Definition of Total Institutions

Erving Goffman coined the term "total institution" to describe environments such as military camps, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals where residents are isolated from the outside world. These institutions impose strict controls over individuals' behaviors.

### The Process of Resocialization

In total institutions, individuals undergo resocialization, which involves breaking down their existing identities and instilling a new set of norms and values through a controlled environment. This process often employs rewards and punishments to reinforce conformity to new group standards.

### Examples of Resocialization

The military is highlighted as a prime example of resocialization, where recruits undergo rigorous training, uniformity in appearance, and a collective identity that emphasizes group loyalty over individuality.

---

## Conclusion

The video concludes by encouraging viewers to reflect on their socialization experiences and consider who has influenced their development. It encapsulates the significance of various socialization agents, including family, schools, peer groups, media, and total institutions, in shaping the individual identity and societal understanding.

Key Takeaways

Socialization is a lifelong process influenced by multiple agents.

Family is the primary source of early social norms and values.

Schools teach both academic skills and social norms through hidden curricula.

Peer groups play a crucial role in adolescence, shaping behaviors and aspirations.

Media significantly influences social attitudes and behaviors.

Total institutions enforce strict resocialization processes, altering identities.

This comprehensive examination of socialization not only sheds light on the influences of various agents but also emphasizes the complexities of how individuals navigate societal norms and expectations throughout their lives.

—-

ASSIGNMENT 01: Reflection Questions

Upload a PDF document, photo, video, or audio file responding to these three questions:

ARTIFACT 02 > Pierre, Len. “Colonial Ideology Graphic: State & Structural Violence Against Indigenous Peoples.”

What does this graphic reveal about Canada?

This graphic reveals how systemically engrained racism is towards Indigenous First Nations, Métis, and Inuit are in the settler colonial nation of Canada.

How might some of these elements show up in your organization?

I am currently unemployed, but I found that they did show up within the previous organization I worked with for approximately a decade (from 2000-2010), the Kwantlen Student Association (KSA). When I first started working with the organization, Indigenous First Nations students at Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU) did not have representation for this group which has traditionally had difficulties accessing post secondary education. Many other student associations across Canada had Indigenous First Nations representatives or liaisons on their society’s board of directors. Five executive positions on the KSA board of directors were assigned the task of representing different groups such as Indigenous First Nations students, although this was problematic as there was no guarantee that say, the Executive Director of Finance, or the Executive Director of Academics, actually identified with those groups in any meaningful way. An executive also had limited time to devote to their own executive portfolio, let alone managing, organizing, and representing a student constituency group. This changed in 2001 when five new non-voting positions were created by the KSA council [Aboriginal Liaison (later changed to First Nations Liaison), LGBTQ+ Liaison, Students of Colour Liaison, Students with Disabilities Liaison, and Women’s Liaison]. Later, in 2003 or so, I moved a motion to add two new liaison positions - International Students Liaison, and Mature Students Liaison. In 2011, these positions were made into voting members of the KSA Board of Directors when a comprehensive revision of the society’s bylaws were passed. However, I personally found that this was weakened as these positions could be appointed by the Board to one of the five executive director positions (President, VP Student Life, VP Finance and Operations, VP University Affairs, and VP External Affairs).

How might your organization be perpetuating colonialism?

WEEK 02: Understanding Indigenous Terminology

Introduction to Culturally Safe Indigenous Terminology

This section focussed on Pierre’s discussion about culturally safe terminology for Indigenous peoples in Canada, as well as how Indigenous terminology is used within a Canadian colonial settler context. It also provides definitions from various sources I found for added context, where appropriate.

It explains the unique distinctions between the following terms:

Indigenous;

Aboriginal;

First Nations;

Métis;

Inuit;

Indian;

Native; and

Settler.

The section also emphasizes the use of respectful language, as well as avoiding outdated or possessive terms, and reviewed frequent misuse of terminology.

It also highlights the importance of a distinctions-based approach and following community preferences.

When in doubt, Pierre stressed the need for professionals (and ultimately all individuals) to seek clarity before discussing cultural safety initiatives as there is always a risk involved in using culturally unsafe or disrespectful language.

Indigenous vs Aboriginal

Indigenous: (adj) “…originating or occurring naturally in a particular place; native. / “…(of people) inhabiting or existing in a land from the earliest times or from before the arrival of colonists.” (Oxford Language Dictionary).

Wikipedia describes how: “Indigenous peoples are non-dominant people groups descended from the original inhabitants of their territories, especially territories that have been colonized. The term lacks a precise authoritative definition, although in the 21st century designations of Indigenous peoples have focused on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territory, and an experience of subjugation and discrimination under a dominant cultural model.”

The United Nations notes that Indigenous Peoples: “…are the descendants - according to a common definition - of those who inhabited a country or a geographical region at the time when people of different cultures or ethnic origins arrived.”

Aboriginal: (adj) “…relating to the Indigenous peoples of Australia or their languages.” / “…

inhabiting or existing in a land from the earliest times or from before the arrival of colonists; indigenous.” (Oxford Language Dictionary).Indigenous Awareness Canada notes how: "Aboriginal people" is a collective term for the original inhabitants of a region and their descendants, such as the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples of Canada.”

Pierre explains how both terms:

refer to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit;

describe the original Peoples of Canada;

are culturally safe in Canada; and

are often used interchangeably depending on the region.

Today, Pierre describes how the term 'Indigenous' is preferred over the term 'Aboriginal' for several reasons such as:

'The term ‘Aboriginal' was imposed by federal government, and as such, many Indigenous leaders historically rejected it;

The ‘Ab-' prefix in 'Aboriginal' implies negation (e.g., 'abnormal');

Pierre also describes how their are concerns that 'Aboriginal' undermines status as original peoples;

‘Indigenous’ is also specifically used to advocate for recognition of rights via international, federal, and provincial legislation, in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) which has been recognized and is being enacted in British Columbia;

The term 'Indigenous' is increasingly used to affirm First Nations identity & history. Specifically it emphasizes unity and solidarity among Indigenous countries, cultures, and communities.

First Nations

Google AI describes how “First Nations are the Indigenous peoples of Canada, distinct from Métis and Inuit, encompassing diverse groups with unique cultures and histories who are the original inhabitants of North America, using the term to replace "Indian" and referring to many separate nations or bands, including both status and non-status people. The term also refers to a legal and political identity under the Indian Act, but is broader, covering all Indigenous peoples south of the Arctic… In essence, "First Nations" recognizes the unique identities and self-governance of Indigenous peoples who are not Métis or Inuit, encompassing diverse nations and communities across Canada.”

The Government of Canada notes that “First Nations are 1 of 3 recognized Indigenous Peoples in Canada, along with Inuit and Métis, where "First Nations people" include Status and non-Status Indians.”

Wikipedia expands on this, explaining how: “First Nations (French: Premières Nations) is a term used to identify Indigenous peoples in Canada who are neither Inuit nor Métis. Traditionally, First Nations in Canada were peoples who lived south of the tree line, and mainly south of the Arctic Circle.”

Pierre noted how:

there are over 600 different First Nations Communities in Canada, from coast to coast to coast; and

in the Province of British Columbia alone, there are 203 First Nations Communities, the highest concentration of First Nations communities nationwide; where

no two Nations are identical, as each Nation is diverse in terms of its culture, history, language, and traditions.

The term 'First Nations' replaced 'Indian' in the 1970s.

First Nations peoples are land-based nations with heritage linked to traditional territories.

Len Pierre identifies as First Nations person descending from the Katzie First Nation, with lineage tracing back to the founding of the Nation.

Diversity

Diversity is defined as: “the state of being diverse; variety.” And, “the practice or quality of including or involving people from a range of different social and ethnic backgrounds and of different genders, sexual orientations, etc.” (Oxford Language Dictionary).

Métis

Google AI describes how: “Métis refers to a distinct Indigenous people in Canada with unique culture, language (Michif), and history, originating from unions between First Nations women and European men, forming a new nation with a strong identity in the Canadian West. They are recognized as one of Canada's three Aboriginal peoples (with First Nations and Inuit) and are defined by self-identification, ancestral connection to the historic Métis Nation, and community acceptance, developing distinct customs and self-governance.”

Pierre described how Métis descend from Indigenous women and Ural settler men - a very distinct nation with unique history, culture, languages, and territories with historical roots are concentrated in the three prairie provinces.

Pierre also identified one common misconception: Métis identity is not simply having one First Nations and one European parent. Specifically, Métis identity requires ancestral connection to the founding Métis nation near the Red River area.

Inuit

The Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada describes how: “Inuit means “the people” in Inuktut, the Inuit language. The singular of Inuit is Inuk, meaning person.” Specifically, the Atlas also notes how: “Inuit are an Indigenous circumpolar people found across the North. In Canada, Inuit primarily live in the Inuit Nunangat — the Canadian Inuit homeland. The majority of the Canadian Inuit population lives in 53 communities spread over two provinces and two territories. Inuit have lived in this homeland since time immemorial.”

In his lecture, Pierre notes how:

Inuit live in communities across Northwest Territories, northern Quebec, and northern Labrador.

Their region is traditionally called Nunigat by Inuit.

Inuit means “the people.” So you never have to say “the Inuit people,” as you would be saying “the people people.”

In the past people called Inuit, “Eskimo,” but today "Eskimo" is a retired term that is not appropriate for non-Inuit to ever use. The preferred term is “Inuit.”

See: Bartko, Karen. “What’s in a name? Elks vs Eskimos debate returns to Edmonton football team.” Global News, 27 May 2025.

ARTIFACT 01 > The Inuit Circumpolar Council of Canada. “Map of the Inuit Homelands.”

A Distinctions-Based Approach / Contextual Use

Pierre explained how:

Distinction space refers to recognizing unique identities of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

A distinctions-based approach acknowledges specific rights, interests, priorities, and concerns of each group, where each group has unique cultures, histories, rights, laws, and governments.

The use of terminology should reflect the specific group involved (e.g., use 'First Nations' if only working with First Nations). People should always try to avoid general terms like 'Indigenous' or 'Aboriginal' if only one group is relevant.

A distinctions-based approaches encourages independent research.

Indian

Pierre discussed how:

The term "Indian" was used in First Nations communities until 1970s.

Elders and older generations still self-identify as "Indian" due to historical usage.

The term also remains in legislative and federal contexts (e.g., Indian Act, Indian status cards, Indian bands).

Non-Indigenous Canadians are strongly advised not to use the term except in legal contexts.

The Indian Act

Pierre described how:

The Indian Act is a Canadian federal law governing Indian status, bands, and reserves.

The law grants federal government authority to regulate and administer affairs of registered Indians and reserve communities.

Indian status is a form of federal identification under the Indian Act. An Indian status card is valid for 7–10 years; renewal requires federal application and approval. The status card system is viewed as being highly racist.

The Indian Act is historically characterized as invasive, oppressive, racist, and paternalistic. Under the Act, registered Indians and reserve communities have fewer rights than newcomers and refugees in Canada.

See: https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/21-things-you-may-not-have-known-about-the-indian-act

Settler

Pierre explained how:

"Settler" describes non-Indigenous persons and is a term that is not based on race or ethnicity.

Rather, n"Settler" is a positional, relational term. Specifically, it indicates ancestors are not from local lands/territories. It implies being an uninvited guest on Indigenous land.

"Indigenous" implies ancestral roots in the land for thousands of years.

The term "settler" can be a trigger for some, but it is important to remember that it is not cultural or ethnic. As such, non-Indigenous Canadians encouraged to understand and use the term accurately.

Do's and Don'ts of Indigenous Terminology

Finally, Pierre noted how people should:

Follow individuals' chosen self-identification terminology.

Use people's preferred gender pronouns and identity terms.

Capitalize "I" in Indigenous for respect, similar to place names.

Be aware of how cultural safety addresses power imbalances through respectful language.

Use "Indigenous peoples" (plural) to reflect diversity, not homogeneity. Pluralization acknowledges hundreds to over a thousand distinct Indigenous cultures, languages, and identities.

Avoid using possessive and other casual terminology:

E.g., "our Indigenous students", "Canada's First Nations people" as possessive terms reinforce power imbalances between institutions and Indigenous peoples. To avoid possessive terms, reverse word order (e.g., "Indigenous peoples in Canada" instead of "Canada's Indigenous people").

Do not use the term "native" as a non-Indigenous person; it is too casual and not culturally safe. Indigenous peoples may use "Native" among themselves, but it is not appropriate for non-Indigenous professionals.

Avoid using the term "Indian" unless contextually appropriate.

— End of Week 02 —

WEEK 01: Introduction

I first registered in Len Pierre Consulting’s online course, INTRODUCTION TO INDIGENOUS CULTURAL SAFETY in May 2025, and moved towards completing it in November 2025. This online journal will serve as a repository for my notes, written reflections, and documentation of assorted journeys taken by me as I navigate the course material.

Course Introduction

The purpose of this course is to provide professionals in health care, education (K-12, colleges, universities), social services, government, legal, and corporate sectors with foundational training on Indigenous cultural safety in colonial Canada. Pierre’s course covers many challenging topics such as: genocide, racism, oppression, state violence, and trauma. In his introduction, Pierre lays out his intention for the course, explaining how he desires: "…to create a safe space for exchanging knowledge, wisdom, conversations, and of course, to support one another in solidarity."

The course is structured into several modules covering terminology, colonial origins of anti-Indigenous racism, as well as cultural safety tools. Pierre noted how he encourages learners to ask questions and engage in respectful dialogue throughout the course. Each module includes a variety of assignments including tests, assignments, or commitments to action. The completion of all assignments is required to pass the course and obtain certification.

About Len Pierre

Pierre is Coast Salish with roots in the Katzie and the Musqueam First Nations. Holding a Masters Degree in Indigenous curriculum and educational design, Pierre is a professor, consultant, and activist who focusses on decolonization and reconciliation. Len Pierre is also the owner and CEO of Len Pierre Consulting, which specializes in Indigenous education and cultural advising. Pierre is also a very authentic and empathetic speaker.